Wittenburg Castle

The site of the castle is located in Lower Saxony in the northwest of Germany. It is above a tiny village, about 15 miles west of Hildesheim. The village was incorporated into the nearby small city of Elze in 1974, but still retains very much its rural character. It took its name Wittenburg from the castle which once occupied the ridge above it, the remnant of a glacial moraine from which important military and trading routes through the valley of the river Leine could be controlled. This moderate ridge is called ‘Vinie’ (also ‘Finie’), both of Latin origin, the first associated with ‘vineyard’ and the second with ‘border’. Which one could it have been? A location for producing wine so far north, or the farthest northern reach of the Roman Empire during the military campaigns by Germanicus into this region in AD 14?

The Chronicles of Wülfinghausen and Wittenburg, 1895[1] by Pastor Heinrich Stoffregen add yet another theory: That the name of the ridge originated from Latin ‘venia’, loosely translated as ‘daily prayer’ and that it was in reference to a prayer-chapel located there. This could only refer to the original chapel which survived the castle and if true, would also give an indication during what time period that ridge may have been named. Could ‘Finie’ also simply signify the end of an ancient moraine there?

The uncertainties do not stop with the ‘Finie’ however, they shroud almost everything else about the castle and its surroundings in mystery and thereby also becoming the source for legends: A place associated with duchesses and countesses, noble widows, pious hermits and robber barons, and finally becoming a place for a brotherhood of monks after a monastery had risen from the ruins of the castle.

Back to the beginning and the castle: The building materials used for its construction were of a local white limestone, white = ‘witt’ in the Low-German dialect of the region, and thus the likeliest explanation for the castle = burg becoming known as the Wittenburg. This and alternate suggestions for the origin of its name are discussed further in this website’s chapter ‘Etymology’

Unfortunately, nothing remains of the castle itself today, we don’t even know how it may have looked. Its building materials have long ago been repurposed, perhaps to terrace the hill and for the subsequent monastery with its large church and the walls surrounding them.

(Photo W.Wittenburg, March 2014)

The origins of the castle are lost in the mists of the past. It is believed by some, that it had existed during the time of pagan Saxons, and at least one writer goes so far as to suggest a fortification may have stood there at the time when the German tribe of Cheruscis repelled the Roman Legions[2] at the start of the 1st century. Perhaps the ‘Finie’ as a border and its strategic placement for controlling traffic from all cardinal directions plus a bit of evidence of Roman presence in Wülfingen[3], 3km to the northeast, lends this some credibility, but without convincing archaeological evidence on site, it is nothing but speculation.

The record becomes clearer following the Frankish conquest at the end of the 8th century and after the arrival of the powerful Billung clan,[4] members of which were subsequently invested as Dukes of Saxony and remaining influential in northwestern Germany into the early 12th century.

There is some evidence about members of the Billungs owning the castle for several hundred years until it was, together with the adjoining chapel and dependencies, donated to the Cathedral of Hildesheim[5] by a ‘Athelheidis ducissa’, which is assumed to have been a Billung heiress.

An article in ‘Alt Hildesheim, 1981’[6] by Roland Webersinn purports to find evidence of Billung ownership in the fact that the castle’s private chapel was consecrated to Saint Willehad, Bishop of Bremen from 787 until his death in 789, and who Webersinn believes, could have been a member of a related branch of the Billungs from southern Germany, where this name, according to him, begins appearing around 800. Willehad as a church patron is indeed unusual in Lower Saxony, but the major problem with Webersinn’s assertion is that Saint Willehad, Bishop of Bremen[7], was a missionary born in Northumbria in the north of today’s England and therefore could not have been a descendant of whatever branch of the Billungs. Webersinn also spots a family connection to the Billungs in Saint Willehad’s successor, Willerich, who succeeded him in 805 after an interim period of several years. His assumption is based on nothing more than the similarity of name. This is as far-fetched an assumption as his other idea, that the name ‘Witegowo’, which he also attributes to a southern German branch of the Billung/Billings, might have been the source of the name for the Wittenburg. Unfortunately, Wikipedia’s otherwise informative entry on Kloster Wittenburg[8]presents Webersinn’s erroneous associations and speculations as encyclopedic facts.

There is better evidence for possible Billung ownership of that castle: Another local historian, Philipp Meyer, Pastor in nearby Wülfingen at the time of his chronicling, tells us in his ‘Burg und Klause Wittenburg’ (Castle and Hermitage Wittenburg) in the Annual of Church History of Lower Saxony 1922,[9] of other Billung properties in the neighbourhood of Wittenburg, – the obedience of Emmerke, the property at Poppenburg, which emperor Henry III gifted to the Hildesheim Cathedral in 1049 after having received it previously from Duke Bernhard (Billung), plus the prefectura which also encompassed Osethe, the latter always mentioned in connection with the castle. A few more Billung properties could be added in that vicinity, but suffice is to say that the Billungs had a strategic interest in being owners of a castle from which to protect these possessions.

What about Saint Willehad then as patron of the castle church? All Meyer writes is, that the Billungs and their heirs had for some reason a close connection to Bremen, and that this was the likeliest reason for Saint Willehad having been chosen by them as the patron for the castle’s chapel.

Whether the new land owners built a new castle on that site or had confiscated an existing one from enemy Saxon nobles, is not known. What is certain is, that the church could only have been built after the end of the 8th century, when Christianity began to hold sway in those lands. That fact supports dating at least the castle’s chapel construction earliest into the beginning of the 9th century. Nothing further is known of the chapel’s or the castle’s history from that time until after they were gifted to the Cathedral of Hildesheim by a mysterious ‘ducissa Athelheidis’. Mysterious, because this name and some vague dates are all that is on record.

Who was the Adelheidis who donated Wittenburg Castle to the Cathedral of Hildesheim?

As to who might have been the generous donor of the Wittenburg castle and other properties to the Cathedral of Hildesheim is a matter of dispute among historians. A number of highborn ladies are thought to have been this ‘Athelheidis’, but the title of ‘duchess’ required to qualify narrows them to a small number of Billung heiressess, spanning a timeframe from the first half of the 11th to shortly after the middle of the 12th century. While theories around circumstantial evidence can be advanced for each of them, – and each chronicler appears to have their favorite – the only clear evidence for the gift, and also the oldest, is the necrology of November 26, 1191 and the subsequent registries of obediences in the Cathedral of Hildesheim. The gift appears to have been already extant at that time from ‘Adelheidis de wittenburch’ and the extent of it is documented as: ‘wittenburg cum appenditiis et duodecim mansos in osethe’ (‘Wittenburg and what belongs to it plus places of settlements totalling about 230 acres in Osethe’ – a village long since disappeared). Unfortunately it contains no information as to when the gift was made. This Athelheidis is also described as ‘soror nostra’ – our sister.[10] Could this be a reference to a nun, perhaps the Adelhaid to be introduced later, who died in the nunnery of Lamspringe in 1162?

It should be noted, that there is no indication of Athelheidis’ noble title in that document, paving the way of all kinds of future speculations, as we will find out. Meyer mentions a further entry in the oldest part of the 12th and 13th century registry of the Cathedral’s obediences[11] It is a bit more detailed and includes the first mention of the castle – ‘castrum Wittenburgh’. It also lists the patronage over the castle’s chapel, the lands and obediences in Osethe and that in recognition of this gift, certain yearly observations were to be performed as well as alms to be given to the poor in memory of ‘Athelheidis ducisse’. It is the first documented evidence of the donor’s rank as that of a duchess.

Meyer suggests that the gifting must have taken place sometime between the first half of the 11th and not too far past the middle of the 12th century due to the form in which it was made, that is, with inclusion of ‘obediences’, a form which would have been unusual earlier and later.

The four female members of the Billung dynasty, or for the 3rd and 4th on Meyer’s list already their Ascanian[12] descendants, who answered to the name of Adelhaid, Athelheidis, (or Eilika, Eleke, Heile, Eila, Eile in Low-German according to him), and of whom he believes one could have been the last owner of the castle Wittenburg are:

- Eilika, (c1005-Dec. 1059), the spouse of Duke Bernhard II of Saxony (c995-June 1059), daugther of the Margrave of Schweinfurt, Bavaria.

- Eilika, (c1080-Jan. 1142), daughter of Duke Magnus of Saxony, (c1045-Aug.1106, grandson of Bernhard II and the last in the male line of the Billungs). She, together with her sister, inherited her father’s private estates and could thus also qualify as the donor. She married Count Otto von Ballenstedt, the founder of the Ascanian dynasty. Her elder sister Wulfhild married Henry IX, Duke of Bavaria, belonging to the dynasty of the Welfs/Guelphs.[13] So both the houses of Ascania and Guelph became heirs to the Billungs.

- Adelhaid (Eilika), c1100-after 1139), daughter of Count Otto of Ballenstedt and Eilika, daughter of Duke Magnus of Saxony. A countess through her father, but of ducal rank through her mother and subsequently again through her husband’s short tenure as Duke of Saxony.

- Adelhaid (Eilika), daughter of Albert the Bear, Margrave of Brandenburg and for a few years Duke of Saxony. Great-granddaughter of Duke Magnus. She died in the nunnery of Lamspringe in 1162.

To emphasize the association ‘Eilika-Adelheid’, Meyer’s list has even those known by their name ‘Adelhaid’ followed by ‘Eilika’ in brackets. He is giving preference to the first Eilika on the above list, the spouse of Duke Bernhard, since other Billung possessions, such as around the nearby Poppenburg and Emmerke, were given up in her generation as well. Nevertheless, Meyer puts forth reservations with regard to the date of the necrology to that of Eilika’s date of death, but allows for the possibility of an error of a few days to have occurred. He also indicates concern about her name only ever appearing in its ‘Low-German form’.

Webersinn, albeit acknowledging Meyer’s work and assumptions with regard to who the potential donor might have been, added yet another Billung Eilica. She must have belonged to a different branch of that family. He also explored relationships of Billung possessions to those of other landed nobles in the region, among them the Esiconians,[14] He comes to the conclusion that an Eilica, one of three only female siblings, who also had Esiconian ancestry and was married into the dynasty of the Nibelungen,[15] may have inherited and then bequeathed the castle to the Cathedral of Hildesheim after her death, assumed to have occurred in the first half of the 11th century. A fifth duchess being added to an already crowded field? On the other hand, the Burgendatenbank[16] (Data Bank of European Castles) narrows the heiresses and bequeathers to either the Adelhaid who died 1162 as a nun in Lamspringe or Eilika, who was Bernhard II’s spouse and died a century earlier, in 1059.

Meyer’s assertion that ‘Adelheid(haid)’ is ‘Eilika/Eilica’ in Low-German has been accepted uncritically not only by Webersinn, but also by subsequent chroniclers as well as by myself in an earlier version of this article. The association does, however, not stand up to closer scrutiny, as a professor of medieval German history kindly pointed out after reading it: While it is accepted that ‘Eleke’ or ‘Elke’ is a Low German diminutive of ‘Adelheid’ through ‘Adelke’ to ‘Elke’, the name ‘Eilika’ is associated with ‘Heilikswint’ or ‘Eilsvit’ and has nothing in common with ‘Adelheid’ The confusion is likely the result of the closeness of the name ‘Eilika’ to the Low German diminutives of ‘Adelheid’ and its variations as can be seen above in Meyer’s brief selection of samples. It also puts Meyer’s remark regarding the exclusive name usage of ‘Eilika’ by Eilika von Schweinfurt into a different light: Her first name was not a diminutive. It is therefore prudent to return to the name ‘Adelhaid’ or rather ‘Athelheidis’, as it appears in the registries of obediences kept by the Cathedral of Hildesheim and assume, that the scribe wrote the name down as it was provided and as he knew it in usage. That would make either no. 3 or no. 4 of the heiresses listed above as one of the likeliest to have donated castle and properties to the Cathedral of Hildesheim, but what Meyer wrote is still true today: ‘Nothing can be established with certainty’, ‘other than it is probable that the Wittenburg castle came through one of these women into the hands of the Cathedral of Hildesheim, and that it was previously owned by the Billungs.’ Eliminating the ‘Eilikas/Eilicas’ from his list merely narrowing the circle of contestants for consideration as donors.

Equally little is known about the reasons why the Billungs abandoned their properties in that region, opening the door to all kinds of speculations by historians. Could it have been a desire to concentrate and consolidate holdings elsewhere, perhaps in recognition of the relative recent acquisitions of these properties and their isolation from other Billung holdings? Webersinn’s’ comments on Reinhard Wenskus’13 list of medieval land ownership in Eastphalia by various other old established noble families are interesting in this context.

Documentation is just as scarce about the function of the castle after it came into possession of the bishop and canons of Hildesheim. Since the Poppenburg’s importance, only 9km to the northeast, increased ever more, it is logical that it was the one receiving attention and resources, the Wittenburg over time becoming irrelevant. Did the latter become a residence for the widows of a local noble family, the Bock of Wülfingen as has been suggested by one of its descendants? Stoffregen detects in his ‘Chronicles’ yet another resident widow and whom he also identifies as the bequeather of the castle: A daughter of Wullbrand I, Count of Loccum-Hallermund, – Adelhaid von Wassel – whose first husband, Count Conrad II von Wassel had a position as ‘Vicedomus’, a sort of worldly administrator/functionary, at the Cathedral of Hildesheim who died between 1176 and 1178. She married Count Günther von Kefernburg in 1180 or shortly before. It is at least possible that she may have taken up residence in the castle 1177 in her first widowhood as has been suggested by various chroniclers, but it doesn’t follow from this that she should have owned and made the bequest of these properties there to the Cathedral after the death of her first husband.

Even Philipp Meyer is, however, originally open to regard this Adelhaid von Wassel as a possible donor of the castle, because of gifts of properties in Wittenburg and Osethe she made in 1163 and before to the monastery of Loccum as ‘Athelheidis comitissa de Wasle’, gifts which were confirmed by Pope Gregory VIII in 1187. The Hallermund/Wassel holdings were indeed significant in that region. In the end, Meyer finds a number of difficulties with this assertion, among them also the then ongoing efforts of the Cathedral to extricate itself from arrangements with reeves who managed its properties. This strongly suggests that bishop and canons would not have entered into new relationships of that sort at the time, only to buy them out again at great cost in 1221.

There is, however, no reason for Adelhaid von Wassel – and perhaps her husband, considering his position at the Cathedral – not to have taken up residence at the castle, even if perhaps only sporadically, while it was already owned by the Cathedral. Based on new documentary evidence available when he conducted his research,[17] Meyer concluded that he had to dismiss her as a potential donor. In doing so, he also cited her title – ‘comitissa’ – countess, as an important point of evidence to rule her out. In this, he relied on the Cathedral’s registry of obediences, where the donor is identified as a ‘ducissa’ – duchess. Stoffregen and other chroniclers may have had access only to the necrology already discussed above, and which names only a ‘Adelheid of Wittenburch’, consequently opening the possibility for almost any noble heiress answering to that name and with a connection to Osethe-Wittenburg to be suspected as the donor. Meyer lastly cites reservations about the sheer size of the gift and its form, – befitting in those days a duchess far better than a countess.

This refutes both the claims made in the Chronicles of Wülfinghausen and Wittenburg, and those upheld a year later in the Journal of the Society for Lower-Saxony Church History, 1896[18] . The authors of the journal’s article even critiqued Stoffregen about his timidity in not confirming Adelhaid von Wassel unreservedly as the donor, claiming proof for it was to be found in the necrologies. Strangely, their criticism does not extend to Stoffregen’s further speculation, based ‘on other sources’ as he called them, that this Adelheid could also have been the widow of Count Berengar of Poppenburg. They then go on to call Johannes Letzner, Pastor and chronicler in the 16th century as their witness. Letzner must have referred to the necrologies of the Amelungsborn monastery, which do indeed mention a ‘Odelhildis comitissa’, but not the one the journal writers thought it to be. Meyer outlines in a footnote in his ‘Castle and Hermitage Wittenburg’ that this was likely a Countess of Poppenburg, the one Letzner identifies as ‘Adela’, widow of Count Berengar of Poppenburg,[19] and which Stoffregen also mentions. Meyer goes on to say that she could not have been widowed in 1177 as indicated by Letzner, since her husband Count Berengar was still alive at that time. Furthermore, where do these necrologies quoted in the 1896 Journal for Lower-Saxony Church History in connection with Letzner proof that ‘the castle Wittenburg was donated by the Countess Adelheid von Wassel in 1177’? To add a bit more context to family connection in those days, possibly also a source for confusing narratives: Berengar of Poppenburg was married to a sister of Count Conrad II von Wassel, Adelhaid’s husband. Incidentally, Conrad II’s father, Count Bernhard also held the position of Vicedomus of Hildesheim, and some sources even claim that Conrad was brother-in-law to Bishop Hermann of Hildesheim.

The Wittenburg castle must have been a popular place as residence for noble widows, at least if various chroniclers are to believed, because there are even more widows alleged to have lived out their final years there. The Bock von Wülfingen, a family propertied in Wülfingen and then also Poppenburg, have already been mentioned. First documentary evidence about them appears in the second half of the 12th century, so the ‘Bocks’, as they were called, and who asserted in the 19th that the Wittenburg may have served their family as ‘widow seat’ could not have placed a date for it earlier than their first documentation. It would more likely have been in the 13th century, which would also refute the speculation that the first part of the castle’s name could have been a derivation of ‘widow’ (see chapter on Etymology), because by that time it had already been named.

Another widow alleged to have been residing in the castle was Oda von Hohenbüchen, spouse of Count Wittekind[2] of Poppenburg, a grandson of Berengar’s brother Friedrich I. She would have been widowed in the early second half of the 13th century. Some accounts also want to see her as the donor of castle and properties to the Cathedral, even though by that time the Cathedral of Hildesheim had already been documented long before as its owner. Stoffregen got it right, when, in writing about this subject with regard to Adelheid von Wassel, he warned that much about it is based on legend. Some of the other stories seem to have come straight out of the realm of fiction.

It appears that Lüntzel was the first chronicler who wrote in his ‘History of the Diocese and City of Hildesheim’ of 1858[10] about the existence and the gift of ‘the duchess Adelheid’, and it took until the ‘Documentary Record Book of the Cathedral of Hildesheim’[17] and Philipp Meyer’s writings in the 1922 ‘Annual for the History of Lower Saxony’ that this thread was more extensively explored. Earlier writers such as Ernst Spangenberg in a contribution to the ‘New National Archive of the Kingdom of Hanover’, 1823, admitted that they had no idea who the previous owners of the castle were, or they made inferences from whatever information was available to them, which were then used by those coming after them as foundations on which to build their own assertions. Adoption and repetition of such narratives was bound to eventually create their own certitudes where certitudes are few indeed, and that also raises a caveat about ‘Athelheidis ducissa’: The Cathedral’s registry of obediences of the late 12th and early 13th century is the only evidence identifying her as a ‘ducissa’. Philipp Meyer was grappling with the sparsity of available documentation as well by inserting an oblique doubt with this comment, that describing as ‘ducissa’ a ‘comitissa’ of the houses of Hallermund, Wassel and Kefernberg would have been extraordinary at the end of the 12th century. He too would obviously have been relieved by confirmation of the donor’s title through additional sources. What are the chances for such secondary confirmation to come forth now, more than eight centuries later? Furthermore, which one of the ladies named ‘Adelhaid’ and with a claim to the title of ‘duchess’ could it be: Adelhaid, (c1100, died after 1139), daughter of Count Otto of Ballenstedt and granddaughter of Duke Magnus, or Adelhaid, daughter of Albert the Bear, great-granddaughter of Duke Magnus, – the latter the Adelhaid who died in the nunnery of Lamspringe in 1162? Could she be the one described as ‘soror nostra’ (our sister) in the necrology of 1191 and therefore have the best claim for having made that bequest? Uncertainty continues to persists.

Of pious hermits and robber barons

Whether the castle did in time become a widow’s seat or not, the narrative about a hermit living there in its latter years near the adjoining chapel is supported by facts. He attracted a few other pious souls through his preaching and good work for eventually a religious brotherhood to be formed, which became the base for the formation of the Augustine Monastery in 1328.

After the monastery had been established, a further tale about the castle’s pre-monastic history took hold: That it was a lair of fearful robber barons, a horror to all travelers in its vicinity. It originated with Subprior Busch’s ‘Liber de reformation monasteriorum’. Busch was Subprior of the monastery in 1435, and after an interval, again a few years thereafter. Stoffregen adopted and disseminated his story further with the chapter on the ‘Wittenburg als Ritterburg’ (Wittenburg as Knights’ Castle) in his Chronicles and made them accessible to a wider readership. Meyer dismisses it, however, as the typical stories circulated after the foundation of many monasteries, namely that the site of the monastery was previously a location of horror. At first blush, it would indeed seem difficult to reconcile the existence of brutal robber barons with the other narratives of the castle: Having served as a widow-seat for high-born ladies and also as the refuge of a pious hermit in the castle’s chapel, let alone to believe that the nearby Poppenburg and the Bishop and Canons of Hildesheim would have tolerated such infringement on trade routes and on their interests.

One would wish it were that straightforward: H.A. Lüntzel’s History of the Diocese and City of Hildesheim, 1858[20] devotes a whole chapter to the ‘Kirchenvogt’, best translated as ‘reeve’ or ‘bailiff’ in medieval terminology. They acted as estate managers, bailiffs/sheriffs on behalf of ecclesiastical property owners, tasks which imperial laws enacted by emperor Charlemagne did not allow clerics to execute themselves, nor were they really equipped to do so. This originally sensible arrangement of separating the spiritual from the worldly, began to break down in the first half of the 12th century.

The reeves’ status was, according to Lüntzel, not equal to that of feudal liege men and the positions were thus not meant to be hereditary. As time went by, this distinction appears to have become exceedingly blurred in practice, the position becoming a family matter and many reeves, instead of taking their status as ‘mild protectors of church property’ seriously, increasingly usurped more power for themselves and behaved like some rapacious feudal lords in their own right. According to Bishop Adelog of Hildesheim, who documented the abuses, they pressed the estates’ peasants for ever more services and payments, and were not shy also to rob, or as we would call it today, to defraud. their nominal ecclesiastical masters. It does not require much to imagine that they may also have extracted a significant share for themselves from merchant caravans passing through the areas they controlled from their strongholds. Lüntzel tells us that the Bihop of Hildesheim was particularly concerned about the ford of the river Leine near the Poppenburg, which at the time also belonged to the Cathedral just as did the Wittenburg.

Attempts were made throughout the 12th century to free the Church from these abusive and oppressive arrangements. The emperor, Frederick I Barbarossa agreed with the ecclesiastical authorities, but, alas, imperial power reached only so far and the chancellery working only so fast. We have it from Meyer that the Cathedral of Hildesheim petitioned the emperor once again in 1180, but that the process dragged on well into the 13th century and was finally resolved with great sacrifice, meaning that only the payment of significant sums of cash could entice the reeves to relinquish their lucrative positions, or perhaps more to the point, their ‘protection rackets’.

It could thus have been possible that while all this was going on, castle Wittenburg might also have served as a seat for widows, and its chapel and annex a refuge for pious hermits, the latter perhaps for nothing more than to appease the canons, but also to portray an image of Christian virtue. On the other hand, these various uses of the castle may not need to have overlapped at all, taking into account the long time period under consideration.

If the bishop and canons of Hildesheim were bothered by these reeves, one can only imagine how it must have been for the locals. This is perhaps where the narrative of ‘robber barons’ originated. The ‘robber barons’ of the Wittenburg were thus in a class similar to those of the Witteburg downriver from Bremen, extracting as much as they could from anyone living in or passing through their jurisdiction.

Who were these reeves? Unfortunately we know almost nothing about them. Could there have been a connection with some of the families associated with the castle following the exit of the Billungs? Chronicler Stoffregen mentions a document of 1221 in which Bishop Siegfried of Hildesheim names a knight, Arnold of Wittenburg. Stoffregen then takes a ‘poet’s licence’ at the end of his Chronicles, where he recites the history of castle and monastery in light verse, and makes this Arnold promptly into a fearful marauding count, – not without adding more confusion, because unfounded speculations about a county of Wittenburg located there had been made before. Another chronicler, Nicolaus Heutger mentions the bishop acquiring from knight Siegfried of Elze and his liege-lord, the Count of Spiegelberg, the ‘advocatia minor in Wittenburg super allodium et duodecim areas’ as well as its bailiwick and 12 properties in 1221[21]. That is all which is known.

As a corollary, this Count of Spiegelberg was none other than Bernhard, Count of Poppenburg, who began to style himself by this name in the second decade of the 13th century. Wittenburg-Osethe were not the only bailiwick he relinquished for quick cash, and the explanation has to do with the Third Crusade of 1189-92. His father Albert, who was a participant on that Crusade led by Emperor Frederic Barbarossa, had sold his interests previously in some other estates already to finance the cost of the undertaking. He hoped, of course, to recuperate his investment and be rewarded amply through bounty brought back after vanquishing the ‘infidels’ in the Holy Land. It turned out to be a lot different. Count Albert, who stayed in the Levant for several years and also took part in the Crusade of 1197, died on the way back to his lands, leaving his son and heir Bernhard in difficult financial straits. It was a time when lords, impoverished through participation in the Crusades, looked at every source of revenue available to them and yes -, some eventually resorted to robbing and looting and thus becoming ‘robber barons’.

Should the robber barons of Wittenburg have existed as described, they were obviously not a serious nuisance to nearby potentates, or it would have invited razing their castle, as was done in many other places. Philipp Meyer surmises that the castle was eventually simply allowed to fall into decay, likely after the reeves were gone, and only the castle’s chapel surviving it all. The castle’ walls and stones may have been used to build the monastery and its pilgrimage church as well as other nearby buildings. It is a rather uneventful end for castle Wittenburg and hidden in the mists of history and legends as is its beginning and the centuries during which it towered over the Finie.

The monastery – Kloster Wittenburg

Nicolaus Heutger was a renowned theologian and historian in Lower Saxony. He did a lot of research on monasteries and churches of the region during his lifetime and produced a correspondingly large body of publications, among them also a commemorative article on the 500th anniversary of the monastery church of Wittenburg.[22], which appears also verbatim in his posthumous signature book ‘Niedersächsische Ordenshäuser und Stifte’. This, and Lüntzel’s ‘History of the Diocese and City of Hildesheim’[10] as well as Stoffregen’s ‘Chronicles of Wülfnghausen and Wittenburg (1) provided much of the basis for the following summary.

A few hermits are known to have lived near the castle’s chapel in 1297, living a pious life and doing good works first under the patronage of Saint Willehad and later the Virgin Mary. Bishop Henry II of Hildesheim recognized the excellent reputation of the small community of then six brothers, by granting them certain privileges in 1316. The success of the small brotherhood also in worldly terms, by being able to add gradually to their agricultural holdings and thereby making the economic survival of the community more secure did, however, not generate admiration everywhere. Philipp Meyer[9] tells us that certain clerical circles detected heresy in the manner in which that community had organized itself. This was a serious matter after the ecumenical council of Vienne, France, convoked by Pope Clement V in 1311, where just such matters were discussed in pan-European terms. It was the reason, and to forestall any future difficulties, why this essentially self-regulated brotherhood was given a more traditional hierarchical form by making the brothers Augustinian canons in 1328 on the advice of the bishop and canons of Hildesheim. It was the beginning of the ‘Kloster Wittenburg, – the Wittenburg monastery.

The monastery never grew to be large, the maximum number of brothers never exceeding eight, but there were obviously a lot more lay brothers for the proper function of the monastery’s agricultural economy. Its good reputation led to further increases of its holdings throughout the 14th century as a result of gifts from wealthy regional nobles.

The first half of the 15th century saw it also become a ‘reform-monastery’. The term ‘reform’ here is not to be confused with the Reformation initiated by Martin Luther almost a century later. That earlier reform movement came out of the Congregation of Windesheim[23] in the Netherlands, a branch of the Augustinians, with its chief reformer being Johannes Busch[24]. He was the driving force in reforming monasteries in Lower Saxony from the base he established in 1435 at the Kloster Wittenburg following his election at the Council of Basle to reform the monasteries in that part of Germany. It was the first monastery in Lower Saxony to accept the Windesheimer reform efforts, not because it was itself in urgent need of reform, but in the contrary, because the Wittenburg monastery adhered to the religious vows upon which it was founded. As a result of that, it even attracted a scholar like Dietrich Engelhus[25] who wrote among many other works a World Chronica – an Encyclopedia – in 1421. Unfortunately this ‘Lumen Saxoniae’ or ‘Light of Saxony’, as he was called during his time, lived there only about a year. He died in 1434 and is buried in the church. Many of the manuscripts which he brought with him to the monastery are now in the State Library of Lower Saxony.

Monastic reforms were seen as necessary then, since many of the monasteries had over the course of time strayed so much into ‘worldly’ matters to make them almost unrecognizable from what they were meant to represent. H.A Lüntzel informs us[26] about the extent of abuses which ranged from disorderly conduct, drunkenness and generally loose morals to avarice and more. It is reported that upon entering one monastery, Johannes Busch was met with threats on his life. Selling indulgences to increase the monastery’s and thereby also the Church’s wealth was, according to Heutger, something in which Wittenburg too displayed its ‘crude side’ of piety for some time. No surprise that the reforms also enjoyed the support of the powerful princes of Calenberg, the cadet branch of the House of Guelph and protectors of Wittenburg.

Johannes Busch executed this reforms in Lower Saxony’s monasteries from 1437-1439 as the Subprior of Wittenburg. He returned in 1454 for another few years to assist in reforming the nunneries in the principality of Calenberg. A notable successor was Prior Stephan von Möllenbeck, who also proved to be an able economist during his long tenure from 1491 until his death in 1525. While other monasteries saw themselves forced to sell properties to survive, he was able to add to Wittenburg’s holdings on account of the monastery’s spiritual reputation. Could, what Heutger called the ‘rough side of piety’, perhaps have played a role in that too? Whatever it was, Prior Stephan could engage in a significant project in 1497 by building the large pilgrimage church, which to this day still dominates the village from the ‘Finie’ above it.

Wittenburg appears to also have managed rather well the difficult times through the Hildesheim Diocese Feud[27] which lasted from 1519-23, a conflict between the prince-bishopry of Hildesheim and the principalities of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel and Calenberg. The Hildesheim Bishops vs, the Guelphs. It was all about the redemption of pledged estates and tax revenues, and as any armed conflict, led to the devastation of villages and countryside, but nothing is reported about Wittenburg in that regard. The treaty of Quedlinburg eventually assigned ownership of Wittenburg to the principality of Calenberg.

More should change was to come after Prior Stephan’s death, when Martin Luther’s Reformation was already radiating from Wittenberg throughout Germany and other parts of Europe. Duchess Elisabeth, regent of the Duchy of Brunswick-Lüneburg-Calenberg, when her son Eric was still a minor, became decidedly Lutheran. It encouraged the monks of Wittenburg to accept the message of Reformation too. This was perhaps also made easier through the zeal emanating from there during the previous century in the reformation of wayward monasteries. Monastic life and the attraction of monasteries began, however, to change irrevocably from what it was and inevitably led to economic decline. To make matters worse, from 1553 on, the brothers had to suffer a ducal official as manager. All he managed was to run it down in his 10 year tenure, so that Duke Eric sold/pawned the entire monastery in 1564 to a Moritz Friese, a confidant, for an enormous sum at that time. Friese managed the Wittenburg estate from then on as ‘Drost’ – administrator -, a post he held apparently until he died there in 1584.

Even before the pawning took place, one monk after another left the monastery, mostly to go to Hildesheim. The economic sustainability of the monastery worsened from year to year, until there was only the Prior and one monk living there in 1564. By 1588 all monastic life had ceased in Wittenburg. From then on, it did not take long for the function of the now abandoned monastery to change into a secular direction. It became an Administrative Seat for Calenberg. There was an attempt in 1629 by a few Augustinian canons to regain the monastery for Catholicism, but that plan failed due to the political constellation at the time during the Thirty-Years War. Protestant Duke Christian-Louis also prevailed in some other challenges about ownership.

Wittenburg as Administrative Seat of the Principality of Calenberg

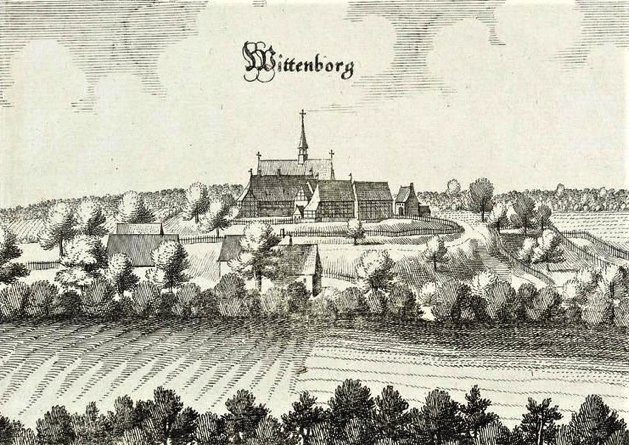

Merian’s copperplate of Wittenborg in 1654 shown here, does not speak of a monastery anymore, but of a ‘Fürstlich Calenbergisch Amtshauss’, a ‘Princely Calenbergian Administrative Seat’- ‘Amt’ in this case signifying an administrative district.

Other than the late-gothic church, none of the monastery’s buildings shown on this picture exist today. What happened to them? None of the chroniclers listed mention anything about it. Stoffregen writes about the significant loss in ‘the great fire of 1741’ of financial assets in form of bonds owed the ‘Amt Wittenburg’ by nearby cities. Did the fire destroy all of the buildings? One thinks that such would have been worthy of recording somewhere, yet there is nothing. The Chronicles of Wülfinghausen and Wittenburg are otherwise exhaustingly detailed about the business of the ‘Amt’ on behalf of the sovereign, its financial ups and downs, listing the names of various ‘drost’-administrators, the particularities about the administration of the Lower Court, discussion about farmsteads, old and new, following a kind of land-reform in the late 18th century. Furthermore, Stoffregen covers the grain mills, forestry and – that an excellent beer was brewed there until the brewery burned down in the latter half of the 19th century. Perhaps the monastery’s remaining buildings after the fire were eventually demolished and anything still usable repurposed, just like with the ancient castle.

Wittenburg becoming a Royal Domain

During that time Wittenburg became a royal domain. It was significantly reduced through the sale of land to new farmers and then turned into an agricultural research and showpiece-estate under the reign of George III, King of Great Britain and Ireland, whose ancestral German holdings, among others, included the Duchy of Brunswick-Lüneburg and the Electorate of Hanover. They became part of the Kingdom of Hanover after the Congress of Vienna in 1814 and remained in personal union with Great Britain until the death of William IV after which that association ceased.

The last King of Hanover, Georg V, commissioned the building of a fairy-tale castle in the neo-gothic style on the Schulenburg mountain, not far from the ‘Finie’, in 1858 as a birthday gift to his spouse Queen Marie. The castle was named ‘Marienburg’ and took many years to complete. Only the best architects, tradesmen and artists were employed with the purpose of making it into a statement and monument to the long history and enduring legacy of the House of Guelph. Unfortunately for the royal couple, they could never enjoy their castle, since construction was disrupted by war with Prussia, which Hanover as an ally of Austria lost in 1866. The kingdom of Hanover became a part of Prussia, and the king went into exile in Austria. The queen, after having spent at least some time in her almost finished castle, was forced to follow the king.

That war was fought elsewhere and had no discernable impact on Wittenburg and the immediate region around it. It must have been different in previous wars, judging from the history of the nearby Hildesheim. When that city suffered through armies laying siege and then engaging in an orgy of violence, plunder and arson, such as during the Thirty Years War in the first half of the 17th century, the fate of the rural population near it cannot have been much different. It may have been better during the Seven Years War in the mid 18th century when French troops coming from Hamelin marched through, and the Napoleonic wars at the start of the 19th, but still, armies on the move through foreign lands have always taken their toll on those who live there.

Back to the Marienburg[28] Visiting it is an unforgettable experience. The castle’s exquisite interior rivals in every way its enchanting exterior, and its keep allows great panoramic views over its surroundings, including to the distant ‘Finie’ on which one can spot the church of Wittenburg.

The original designer and architect of the Marienburg was master builder Conrad Wilhelm Hase, who was famous as a neo-gothic revivalist. It is no surprise therefore, that traces of his work can also be found in the Wittenburg church. Long overdue repairs became necessary to the 300 year old building already in 1800. Among other work, the roof ridge was significantly lowered and covered with tiles. This changed the proportions of the church, now making it look more like a chapel from afar. It was a lot better, however, than the alternative proposed a few decades earlier – and fortunately rejected by the authorities: That the church be demolished entirely! It took another half a century for a new bell tower to be put on the roof, smaller than the original, but nevertheless completing the ensemble. again. Then, in the 1880s, Hase occupied himself with the renovation of the interior, careful to remain true to the church’s late-gothic style.

According to an essay on the ‘History of Wittenburg’ by a graduation glass of 1971[29] which unfortunately does not list the name of the school or town, the church on the Finie suffered more than from long neglect of maintenance: The western part of the church, in which, during monastic times the lay folks could worship, in contrast to the smaller, separated, and older eastern part reserved for the monks, was used for the housing of sheep since 1590. The disrupting bleating of sheep during services finally got Pastor Bauer of Wülfinghausen in 1867 to petition none other than the King of Prussia himself to restore the whole church as a house of worship again. It took five years until the request percolated up and down through the various bureaucracies, and the administrators of the Domain of Wittenburg finally acquiesced. The sheep were gone, but the western part of the church still remained to be a storage place.

Fortunately help was coming eventually from the highest order to bring the church back to its original function: From Kaiser William II personally. He came on the Wittenburg ‘ Finie’ in September of 1889 to watch from there his beloved ‘Kaiser Manöver’ – military manoeuvres – taking place in the plains of the Leine Valley. Being fascinated with all things medieval, he also visited the church. Apparently he did not appreciate all that he saw, and promptly ordered the church to be restored further to its original function.

Incidentally, for those interested in learning more details about those ‘Kaiser manoeuvres’ involving Wittenburg, Mehle, Sorsum, Boitzum, Wülfinghausen and Osterwald can read about it in the ‘Allgemeine Schweizerische Militärzeitung, 1889’[30] (Journal of the Swiss Military), the official organ of the Swiss Army. The Swiss had obviously always been keen observers of events beyond the border of their small country in the heart of Europe.

The two World Wars, as in so many other places, left deep scars here too. The memorial in the shadow of the Wittenburg Church to the many who never returned to the villages of Wittenburg, Sorsum and Boitzum is a grim reminder. World War II also brought the war into these lands again when tanks of the US 9th Army began rumbling from Hamelin through the villages and Elze in early April 1945, on their way to bombed out Hildesheim and beyond. The war’s aftermath witnessed a large influx of refugees into the region from formerly eastern territories of Germany, which were resettled and integrated chiefly in the larger centres. For a time, Catholic Mass was celebrated anew in Wittenburg’s church to also provide spiritual support to Catholic refugees from the east.

Later on came the restructuring of political entities: What was possibly once at the most northern reach of the Roman Empire, was once part of pagan Saxony, Frankish Saxony and the Holy Roman Empire, the dukedoms, the Napoleonic interlude, Hanover and Prussia, – the Kaiserreich, the Republic, the Nazi-Nightmare -, became after almost two millennia the ‘Land Niedersachsen’ – ‘Lower Saxony’ in the Federal Republic of Germany. Lower Saxony and the churches then negotiated a significant agreement in 1955, the ‘Loccum Contract’ – named after the monastery of Loccum, where it was signed -, to govern the relationship between State and Church. It had significance for Wittenburg, because it allowed the old Wittenburg monastery church to be transferred to the local parish. In a sense it was the final act in the ‘dissolution’ of the monastic properties, the last remainder of the royal domain, after all else was already sold off to individual farmers in 1908

Wittenburg becomes part of the city of Elze

1974 brought the amalgamation with the small neighbouring city of Elze[31], which also included the villages of Esbeck, Mehle, Sehide, Sorsum and Wülfingen. Wittenburg is the smallest part of Elze[32], but it still retains a degree of self-government, just like the other villages.

Last but not least, a society was formed in 2000, ‘Freunde der Wittenburger Kirche’[33] (Friends of the Wittenburg Church). The church and ensemble on the Finie, including the partly restored monastery enclosure wall are now protected monuments. The Friends’ mission of which is to act as the church’s charitable guardians, to look after its upkeep, its immediate surroundings, the organization of cultural events, and to continue the tradition of all those who cared about that church and the long history played out on and around the ridge called ‘Finie’.

December 2020, edited February 2021, January 2023

https://youtu.be/-lGuMZ2p0lk

References/Links

[1] Chronik von Wülfinghausen und Wittenburg, 1895, (Chronicles of Wülfinghausen and Wittenburg), Heinrich Stoffregen: (pages 55-83 pdf and poem on W., pages at bottom of their website.)

[2] Wenn Steine reden könnten, (If stones could talk), Ernst Andreas Friedrich, 1998, Bd IV, page 90

[3] Eine Siedlungsstelle der römischen Kaiserzeit by Wülfingen an der mittleren Leine, Die Kunde, Zeitschrift für niedersächsische Archäologie, 1983/84 Nr. 34/35, Roland Webersinn, pages 237-245 (A site of settlement during the time of the Roman Empire at Wülfingen on the middle Leine, Die Kunde, Journal for Archaeology in Lower Saxony)

[6] Alt Hildesheim, Bd. 52/1981, Roland Webersinn, pages 7-10

[8] Kloster (Monastery) Wittenburg

[9] Burg und Klause Wittenburg, Jahrbuch der Gesellschaft für niedersächsische Kirchengeschichte, no. 26, 1922, Philipp Meyer, pages 52-53, 57-58

[10] History of the Diocese and City of Hildesheim, H.A. Lüntzel, 1858, page 40

[11] Urkundenbuch des Hochstifts Hildesheim und seiner Bischöfe, Bd VI, Janicke-Hoogeweg, Page 990

[15] Sächsischer Stammesadel und fränkischer Reichsadel, 1976, ( Genealogical table, Old Saxon and Imperial Frankish Nobility) Reinhard Wenskus

[16] EBIDAT – Die Burgendatenbank (The Data Bank for European Castles)

[17] Die Urkunden Wittenburgs bis 1398 in Janicke-Hoogeweg, Urkundenbuch des Hochstifts Hildesheim und seiner Bischöfe, Bd I bis VI, 1896-1911

[18] Zeitschrift der Gesellschaft für niedersächsische Kirchengeschichte (Magazine of the Society for Lower-Saxon Church History), page 257

[19] Letzner, Hildesheimer Chronik Bd II, Page 54 and Bd III, Page 16

[20] Geschichte der Diöcese und Stadt Hildesheim, H.A. Lüntzel, 1858 (History of the Diocese and City of Hildesheim) Pages 6-15 ‘Der Kirchenvogt’

[21] Urkundenbuch des Hochstifts Hildesheim, VI, Nr. 762, Page 2 ref. on 500 Jahre Klosterkirche Wittenburg

[22] 500 Jahre Klosterkirche Wittenburg, 1997, Prof.Dr. Nicolaus Heutger

[23] Congregation of Windesheim

[26] Geschichte der Diöcese und Stadt Hildesheim, H.A. Lüntzel, 1858 (History of the Diocese and City of Hildesheim) Pages 433-450 ‘Magnus 1424-1452’

[29] Die Geschichte Wittenburgs, 20.3.1971, (The History of Wittenburg, Graduating Class of Grade School, direction Pastor Herbst) Die Abgangsschüler der Volksschule unter Leitung von Pastor Herbst, Wülfinghausen

[30] Kaiser Manoever September 1889 Allgemeine Schweizerische Militaer Zeitung/General Swiss Military Journal, no. 44, Nov 2,1889